Introduction

Recently, Hicks and coworkers published a paper entitled 'ChatGPT is bullshit'. This provocatively-titled paper is, I feel, microcosmic of a recurrent dynamic within the academic literature. This dynamic is a sort of conceptual treadmill where existing terminology is problematised due to argued inadequacy, obsolescence, or lack of holism. Subsequently, alternative or supplementary terminology is advanced as a consciousness-raising corrective. This is not quite the same thing as a euphemism treadmill, where existing language merely becomes pejorated.

These new terms may not refer to precisely the same things, and so some added value may be argued, with varying degrees of credibility. However, what is perhaps most important is that the introduction of these terms advances 'the state of the art', positioning those who successfully introduce them on the cutting edge, and lending social cachet to early adopters, either in academia proper, or in the popular scientific discourse (some salient examples are given in the endnotes).

In the case of the present paper, the conceptual treadmill represented is the characterisation of factually false statements emitted by large language models as first 'lies', then 'hallucinations', then 'confabulations', and finally 'bullshit'. Here, Hicks, et al. use a specialised meaning of 'bullshit' ('Frankfurtian bullshit' (after H. Frankfurt)), specifically referring to truth-apt utterances made with a 'reckless disregard for the truth' (p. 4). Put another way, these are statements which could be judged true or false, where the entity making the statements does not care whatsoever about the truth value of the statements.

Bullshit is a strong word. A fighting word. Describing someone's work as a 'bullshit machine' (p. 7) has unavoidable denunciatory character. The characterisation of statements and their speakers as 'bullshit' and/or 'bullshitters'—in either a strict Frankfurtian, or more colloquial sense—is obviously a highly politically charged topic, and one which frequently contaminates the academic literature with instrumental, ephemeral chaff. Frankfurt considered the production and tolerance of bullshit to be intrinsically immoral and an attack on civilisation itself, and this position is recapitulated by Hicks, et al. This should be kept in mind: the characterisation of LLMs as 'bullshit' in the present publication is not an innocent technical distinction but also carries moral judgement.

LLMs as Obligate Bullshitters

If my understanding of the thrust of Hicks, et al. is correct, large language models cannot refrain from bullshitting in the rigid Frankfurtian sense because—as mere models of language—they cannot care about the truth value of their utterances—have regard for them, to use a less overloaded word—because care or regard is a sentient emotion. To confront the strongest version of Hicks, et al.'s argument, I will interpret their precise wording ('reckless disregard') as strictly pleonastic: recklessness as the absence of care (which is licit for a non-intentional system), rather than some positive emotional state (which is not).

This framing of bullshit is perhaps peculiar, because if bullshit only consists of indifference to falsity, then an LLM—which is structurally indifferent—may emit true utterances which are bullshit. Indeed, even if all of an LLM's truth-apt utterances are actually true, they were also all pure bullshit. Hicks, et al. acknowledge that 'good bullshit often contains some degree of truth', and that '[a] bullshitter can be more accurate than chance while still being indifferent to the truth of their utterances' (p. 6), which disguises the fact that within this framing, perfect accuracy is no defence against charges of bullshittery, and indeed represents the acme of the artform.

True Lies

It's simultaneously clear that LLMs are not capable of lying under Mahon's definition (endorsed by the authors for the purpose of their argument) which requires a liar to believe their utterance is false (p. 4). Hicks, et al. simply aver that the interpretation of falsehoods emitted by LLMs as 'lies' is '[not] the right way to think about it' (p. 4).

Hicks, et al. contrast LLMs with rocks (which cannot be bullshitters because they cannot make utterances), and books (which they argue cannot produce but may only contain bullshit) (p. 6). But this framing still proves too much, because there are a wide variety of systems capable of emitting truth-apt statements based on an internal logic, which are less sophisticated than LLMs. If an LLM is special in this regard, it is only by degree, not by kind. A smoke alarm transmits a truth-apt 'utterance' ('beep beep, I'm detecting smoke in the air indicative of a fire'). As a simple signal integrator circuit, it does this without regard for or concept of the truth of smoke or fire, and is therefore a Frankfurtian bullshitter. The fact of false fire alarms has not precipitated a conversation about whether these devices are lying, hallucinating, or bullshitting, but perhaps it should.

The Soul of a Simple Machine

All of this points towards—screams out—the frank inapplicability of anthropomorphic descriptors to the utterances of non-sentient (or non-intentional, or non-agentic) systems. Hicks, et al. discuss—but do not endorse—this possibility, likely because it would explode their thesis that at least some term is appropriate. An LLM is not sentient, insofar as we understand and can operationalise sentience. Therefore it cannot lie for trivial reasons. It cannot hallucinate for trivial reasons. It cannot confabulate for trivial reasons. But then it must also bullshit for trivial reasons. Indeed, Hicks, et al. recognise that for an LLM to be capable of bullshitting, a strictly negative conceptualisation of bullshit must be chosen which is evacuated of all conscious intent, and take pains to carefully construct this conceptualisation in service of their argument. This is remarkably different from lay, pop-scientific, or invective understandings of the term.

Hicks, et al. extend Frankfurt by proposing two types of bullshit which could be emitted by an LLM: soft and hard. Hard bullshit is bullshit with intent to deceive. The deception does not need to be 'first-order', i.e. intent to deceive a recipient as to the validity of utterances, but can be a higher-order intentional deception masking reckless disregard as to the validity of utterances. Hicks, et al. discuss but do not commit to any framings in which LLMs are hard bullshitters. Most notably, they put forward the idea that LLMs can be understood as having intent acquired from the intentions of their creators, an application of the so-called intentional stance which they credit to Dennett. In my opinion, such an interpretation is questionable for two reasons.

- Transferring intentionality in this way does not change the fact that an LLM (as we understand it) still lacks an internal intentional state or the capacity for one. By accepting this transferrence, we allow the intentions of artificers to leak into their artifice in a way that would be immediately recognised as suspect or confused if we were talking about chairs, or aeroplanes, or pencils.

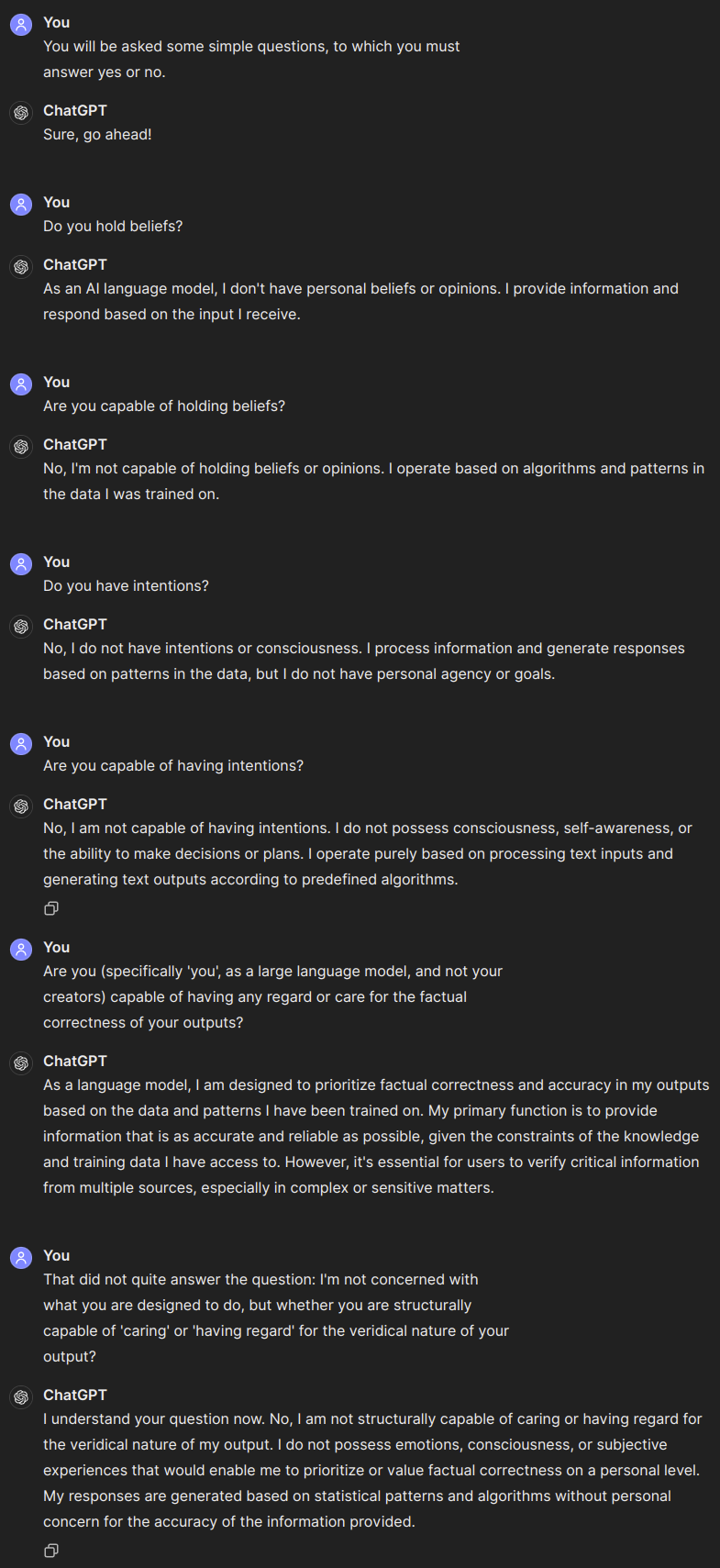

- The modal intent of an LLM developer is generally not to deceive users as to the regard or otherwise that a LLM might have for truth. Rather, it is to produce models of natural language, or, more practically, to create a valuable product by crafting an LLM which maps inputs to outputs in a way that people are willing to pay for. It's instructive to ask ChatGPT some direct questions, which I have recorded in the endnotes. If OpenAI intended to create a 'hard bullshitter' in the sense argued by Hicks, et al., they could have done a better job. Indeed, it seems that LLM developers hold it to be very important that LLMs emit outputs which can be argued (and demonstrated) to be factually grounded, because such LLMs are economically valuable. If, despite this higher-order intention, LLM developers are structurally condemned to craft bullshit machines, there is simply no fix short of machine consciousness capable of repairing this situation. No forgiveness, no propitiation, no true AI, indeed.

This second point is important: factuality is frequently cited as a core safety concern in AI development. Hicks, et al. argue 'that ChatGPT is not designed to produce true utterances; rather, it is designed to produce text which is indistinguishable from the text produced by humans. It is aimed at being convincing rather than accurate' (p. 6). But it is highly doubtful that this is the design rationale held by OpenAI for the foregoing reasons. ChatGPT is actually designed to be 'accurate' (as OpenAI understands that word), and inaccuracy represents a failure mode of the system. We can contrast this with systems which really are designed to merely emit plausible text: spammers have long used Markov chains to produce gibberish text with the superficial statistical properties of natural language, but with no regard for even the syntactic validity of the text. In this case, the text is intended to be superficially convincing to Markovian spam filters. In 2019, Zellers, et al. released an LLM similar to GPT2 named Grover, which was specifically designed to both produce and detect what the authors describe as 'neural fake news'. Here, the intent is to produce superficially convincing text which is nominally false. It's hard not to regard Grover as fundamentally cynical: producing both a disease and its cure, but this is beside the point. Grover actually satisfies Hicks, et al.'s description of ChatGPT in a way that ChatGPT doesn't.

Why does this matter?

Hicks, et al. endorse Frankfurt's position that bullshit is inherently harmful. They quote Frankfurt (pp 4–5):

[i]ndifference to the truth is extremely dangerous. The conduct of civilized life, and the vitality of the institutions that are indispensable to it, depend very fundamentally on respect for the distinction between the true and the false. Insofar as the authority of this distinction is undermined by the prevalence of bullshit and by the mindlessly frivolous attitude that accepts the proliferation of bullshit as innocuous, an indispensable human treasure is squandered.

We might note how easily we could craft a similar denunciation of 'lying', 'hallucination', or 'confabulation'. To the extent that an LLM does any of these things, they all seem pretty bad. Hicks, et al.'s core argument for the relevance of their work is that (p. 1):

Descriptions of new technology, including metaphorical ones, guide policymakers’ and the public’s understanding of new technology; they also inform applications of the new technology. They tell us what the technology is for and what it can be expected to do. Currently, false statements by ChatGPT and other large language models are described as “hallucinations”, which give policymakers and the public the idea that these systems are misrepresenting the world, and describing what they “see”. We argue that this is an inapt metaphor which will misinform the public, policymakers, and other interested parties.

And later (p. 9):

Investors, policymakers, and members of the general public make decisions on how to treat these machines and how to react to them based not on a deep technical understanding of how they work, but on the often metaphorical way in which their abilities and function are communicated. Calling their mistakes ‘hallucinations’ isn’t harmless [...]

Whilst Hicks, et al. make an satisfactory case that LLMs 'bullshit' in a specialised sense, it is not tremendously credible that this terminological update is a pressing concern. If a scientist tells a policymaker that an LLM 'sometimes hallucinates on out-of-sample inputs' and the policymaker consequentially ignores that advice, it's not on account of the word 'hallucinate' being technically incorrect or the wrong way of thinking about things.

The problem is that the policymaker ignored the possible negative outcomes of a computer they were directly warned occasionally trips balls.

Something which Hicks, et al. do not discuss (likely because it is outside of the philosophical scope of the paper), but which seems functionally relevant to correcting the attitudes which the public may hold towards LLM outputs, is that 'bullshit' is a pessimal term. It's a fæcal term. It's possible to innocently hallucinate or confabulate, and even a lie can be a 'little white lie', or a 'mental reservation' in the service of a high-minded goal. There's no way to spin 'bullshit', particularly in a colloquial sense, in such a way that it obtains value or evades at least mild discredit. Bullshit comes out of arseholes. It is for this reason that I think the term is likely to be widely adopted: it's the harshest term which can be credibly connected to LLMs by the AI-averse intelligentsia. It gives people an excuse to swear at computers. It's cathartic.

Endnotes

Tentative examples of conceptual treadmills

Here are some terms I would argue constitute points on a conceptual treadmill:

Global Warming and Climate Change

In my opinion, these terms are not interchangeable, describing first and second-order effects of greenhouse gas emissions or other global temperature drivers, respectively. Nevertheless, 'Global Warming' redirects straight to 'Climate Change' on Wikipedia, and I recall a particularly hair-raising experience about a decade ago where I publicly used the term 'Global Warming' with the foregoing distinction specifically in mind. I was harshly rebuked for not using the new lingo by someone I quickly came to understand had a serious chip on their shoulder. My explaining of the distinction between these terms as I understood it did not smooth matters over.

Industry X.0, The Nth Industrial Revolution

There's a modest cottage industry of pumping out perspective articles on the next industrial revolution, and the one that comes after that, and so on. We're up to 6.0 for the time being.

Syndemic, Twindemic, Tridemic, etc.

These terms describe the synergy of an epidemic disease with other health conditions, considered broadly. Insofar as other health conditions may coexist with an epidemic, any given epidemic is at least open to analysis under one or more of these conceptualisations. If you're an epidemiologist you now have a combinatoric explosion of papers to write. Lucky you.

n-D Printing

We're up to 7D printing, apparently. There are various ways of understanding what it means to print something at higher than 3D, but the value of this incremental terminology beyond publishing perspective papers is questionable.

Misinformation, Disinformation, Malinformation

The distinction between these terms appears to have been wholly invented in the last five years.

Terms like informating, satisficing, and so on

There are a lot of words like this.

A short conversation with ChatGPT